Growing up, if it was time that pruned our curiosity, should we blame time?

The other day was Book Day, and many publishers, knowledge providers, and knowledge bloggers were promoting all sorts of books, and we may not worry about getting our money's worth out of the book, but about whether we'll have time to read it once we buy it.

After saying goodbye to our student days and going into the workplace to work, we have less and less time to read. In our free time, we may still be able to read some articles (like the one you are reading this one I wrote), listen to some podcasts and watch some videos.

But there's also a voice saying, "These are fragments of content, they're worthless! If you want to learn you'd better go to a book, preferably one of those classics or a big one!"

Good lord, whoever said that must not want you to study properly, that's clearly discouraging.

In today's post, instead of talking to you about what to read, or how to read, I'm going to talk about our motivations for reading. **

A couple of weeks ago, I listened to a podcast, which was probably an interview with up owner Lao Jiang, talking about content creation, the B site ecology, etc. Then they got to talking about media. The guest, Jiang, said, "I'm a McLuhan believer," and then they started talking about cold media, hot media, and other words that I didn't even understand.

I listened to the entire podcast mostly without fail, except for 'McLuhan' and 'medium' which felt like the last piece of the puzzle that turned into a small seedling that was buried in my mind. So for a while after listening to the podcast, I couldn't help but explore and figure out these two words. Then I found a different perspective on the world from Understanding Mediums, and my cognitive boundaries expanded a bit as a result.

Looking back at my journey from a foreign concept to a gradual understanding, the biggest driving force that has continued to drive me deeper is curiosity.

The formation of curiosity

In "The Zen Garden Behind the Broken Mountain Temple", the poet Chang Jian walks through the bamboo grove in the temple to the deep backyard and finds that the Zen room where he chants Buddhist sutras is located deep in the flowering trees in the backyard. The poet then sings his praises and writes a great line that has been handed down through the ages, "Where the winding path leads to the seclusion, the meditation room is deep in flowers and trees.

Why do people find such hidden 'curved paths' beautiful?

Why do people find such hidden 'curved paths' beautiful?

Scientists at the California Institute of Technology monitored students by scanning them and found that the 'caudate nucleus' in the brain, which details the neurons that transmit dopamine, is activated when students are triggering curiosity.

That is, when curiosity is aroused, it synchronizes the stimulation of the caudate nucleus, which then secretes dopamine that makes us happy, which in turn makes us feel pleasure.

For our human ancestors, the more we knew the more likely we were to survive. Humans need to anticipate their environment, animal habits, and behavior, which requires a strong memory storage capacity, as well as the ability to consciously acquire knowledge. Curiosity, that is, is the emotional drive that drives humans to acquire knowledge.

But does having a curious mind immediately lead to reading complex specialized books? Or is it the same question as at the beginning: does learning have to be systematic, and does reading have to be a classic monograph? I don't think so. Curiosity should be cultivated gradually, not in one step.

Ian Leslie divides curiosity into pastime and cognitive.

- Diversive curiosity (diversive curiosity) manifests itself primarily in a physical sensory fascination with new things. For example, we like to travel to different places and make new friends. It keeps us exploring the outside world, endlessly enjoying the new and the old. Many internet products, too, are taking advantage of such human curiosity and leading users to swipe videos addictively.

- Cognitive curiosity (epistemic curiosity), on the other hand, is a deeper, ordered, purposeful inner drive. It is the source of our ability to sustain inner satisfaction and pleasure, and is an important factor in our ability to continually improve our perception and understanding of the world.

"Cognitive curiosity" is a transformation from "pastime curiosity ". The original interest in learning something new arises from 'pastime curiosity', and then it is transformed into cognitive curiosity as it extends to purposeful questions with deeper understanding. It's like when you start out relaxing through music and then, because of an opportunity, you start to study the rhythm, instrumentation, and music theory of music.

Curiosity is the original motivation that leads us to knowledge and summarizes the laws. But sadly, as we grow older, our curiosity becomes less and less, and we can no longer afford to take an interest in reading. It is like a genie that eludes us and disappears without our notice as we grow up.

I can't help but wonder, where did it go? How did it disappear?

Vanishing curiosity

I was on 'Instant' the other day and saw someone ask the question: why do most people gradually lose their curiosity as they get older? There were quite a few comments below as well. I could feel that this was a sentiment shared by many people who have 'grown up'.

I believe that curiosity disappears for two main reasons: pruning by age and truncation by technology, the former being internal and the latter external.

I believe that curiosity disappears for two main reasons: pruning by age and truncation by technology, the former being internal and the latter external.

Internal causes: pruned by age

When still a child, our perception of the world is extremely rich.

The baby brain, although smaller than an adult, has millions more connections of neurons in its brain than an adult. In the eyes of a child, there is curiosity everywhere; they do not know what is dangerous and what the rules of human society are.

But as it grows slowly, the child gradually learns and adapts to human civilization and social order. Time is like a pair of scissors; it automatically prunes the disorderly and faulty branches of neural connections in the child's brain. Time prunes the neural connections and also prunes curiosity until adulthood can automate the problems that are taken for granted.

What is the consequence of "automated information processing"? We will gradually fall into a closed perception of logical self-accuracy.

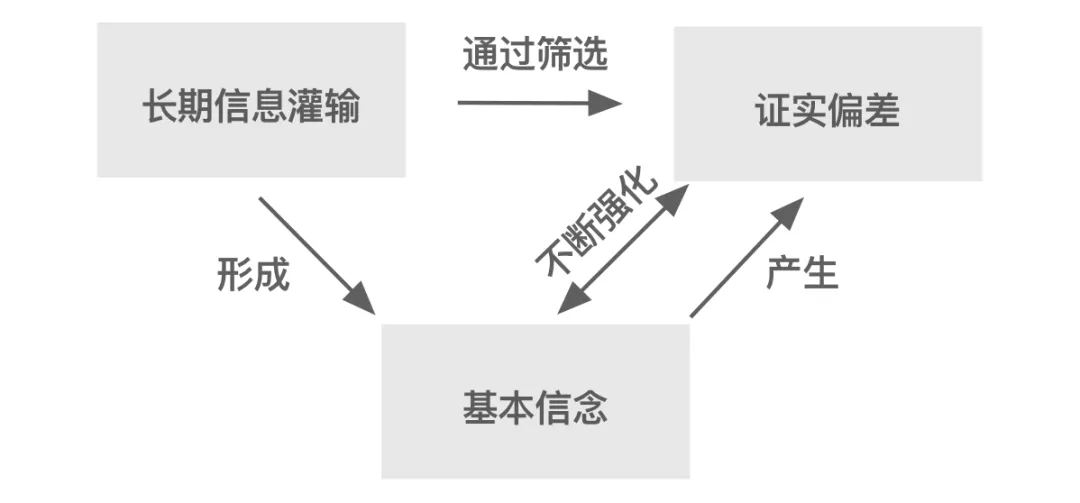

From childhood, we are influenced and indoctrinated with long-term messages by our family, friends around us, and other environments. We construct our own perceptions of the world and form basic beliefs as a result. But inevitably, we receive information that is necessarily biased and inaccurate, and people prefer to accept information that is consistent with their own ideas and positions (cognitive bias), thus gradually closing off their perceptions.

It has been said that many people die at 25 and are not buried until they are 80. After the age of 25, curiosity is no longer active either. Let's ponder the question further, should we blame time for pruning our curiosity?

It has been said that many people die at 25 and are not buried until they are 80. After the age of 25, curiosity is no longer active either. Let's ponder the question further, should we blame time for pruning our curiosity?

It shouldn't. Time is neutral, and it is because of its presence that we wonder and think.

I remember when I was at my busiest at work before, I was pretty much worrying about work all the time I was awake, except for sleeping. I was under tremendous pressure, my brain hurt from dealing with the ponderous and various priorities, and when I came home from work, instead of wanting to read and study, I would have 'vicarious entertainment' and watch anime until late. When it comes to weekend vacations, I don't want to use my brain at all, I just want to lay around, watch dramas and variety shows.

Our curiosity is constantly pruned because of social discipline; and our curiosity is gradually depleted because of busyness.

External causes: technically truncated

"Where there is gain, there is cost."

Humans walk upright and have a huge brain capacity, giving us a clear survival advantage, but difficult births, hemorrhoids, varicose veins, and herniated discs are common health problems that come with it. Clearly, none of these problems were brought about by natural selection; they are simply a byproduct of the two traits of walking upright and having a large brain.

Technology is no different, and because we enjoy the convenience it brings, we pay a corresponding price.

In Understanding the Medium, McLuhan suggests that technology is an extension of the human being. For example, clothing is an extension of the skin, the wheel is an extension of the foot, the newspaper is an extension of the eye, the radio is an extension of the ear, and the medium is an out-of-body extension of the person. BUT "Where there is a gain, there is a cost", extension means "truncation ".

When the body is stressed by hyperstimulation, the central nervous system protects itself by amputating or isolating the organ, sensation or skill that is making the person uncomfortable.

--McLuhan

As in a sci-fi movie, a half-man, half-machine 'cyborg' hybrid.

He has strength and functionality beyond that of a normal human, but at the cost of amputation of what would have been his body before he could be fitted with robotic arms and legs.

If you still don't quite understand the meaning of "human extension" and "truncation", let me give you another example: WeChat allows us to communicate with people in different places anytime and anywhere It flattens the world we live in compared to the old way of correspondence, and the phone is like an organ that extends from our body and connects us to other people's organs through the internet.

If you still don't quite understand the meaning of "human extension" and "truncation", let me give you another example: WeChat allows us to communicate with people in different places anytime and anywhere It flattens the world we live in compared to the old way of correspondence, and the phone is like an organ that extends from our body and connects us to other people's organs through the internet.

What's the cost of efficient, instantaneous connectivity? A few people sitting face to face, but each talking through their phones because of WeChat, and what it truncates is the opportunity to look up at the world and communicate with the people around us in reality.

Today, the Internet's search capabilities and algorithms make it easy to find any information you want; you may have just typed the first word and a list of the questions you are most likely to search for pops up under the search bar, and before you even start typing, the search platform has already presented you with what you want.

It's like Doraemon's free gate, you can think about it and the next thing you know, you're there. The scenery along the way to your destination, or an impromptu exploration in the middle of the journey, is even more enjoyable and precious.

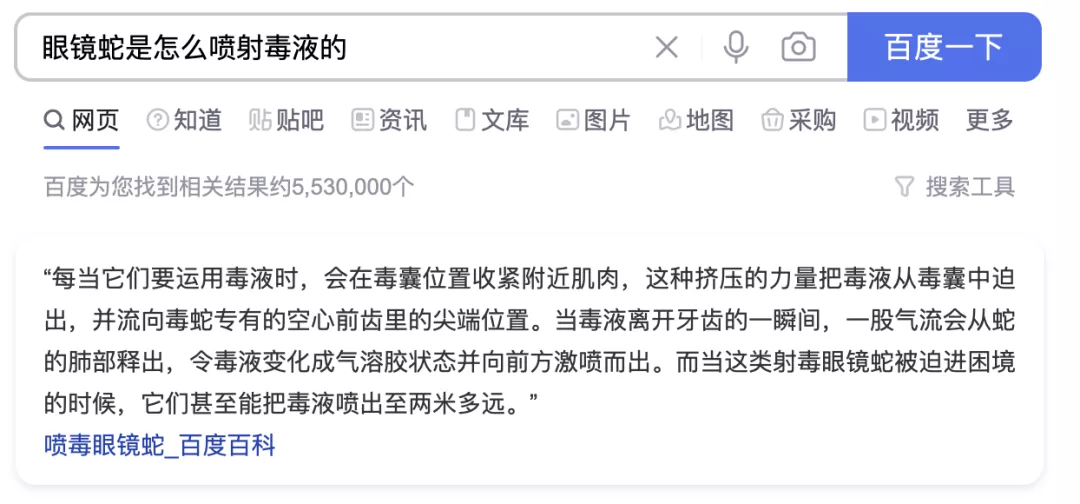

If it were 15 years ago, if we wanted to learn how cobras ejected venom, we would have bought the encyclopedia of animals and gone home and slowly flipped through it, and we might have gotten interested in other critters as a result, and then thought about the evolution of the animals and their habitats and so on.

And now, we can get targeted and definitive answers directly through 'search'. After reading the answers, I may be like the farmer who caught his prey and collected his gun and went home.

And now, we can get targeted and definitive answers directly through 'search'. After reading the answers, I may be like the farmer who caught his prey and collected his gun and went home.

Search and algorithmic techniques that intercept the possibility of you stumbling upon new knowledge and generating curiosity.

Glowing Pixie

Going back to the very first reading question, do you need to go through the system right from the start? It's naturally best if you can do it and enjoy it, but what if you can't? Don't force yourself, just take it step by step.

Curiosity accompanies us left and right like a glowing pixie after each of us is born. The pixie is the size of a basketball, glowing with a warm white light and joyfully alive all around. It constantly stimulates us to learn about the real world, to expand the boundaries of our knowledge, and to adapt to the society in which we find ourselves. But as we grow up, we become more and more 'worldly', busier and busier, or addicted to the dazzling digital information.

We grow up, curiosity "meritocracy"has up**.

Because it was left out, the Curious Pixie grew weak and is now a grain of light, lurking somewhere in an obscure corner of the brain, waiting for us to wake it up. In the beginning, the Curious Pixie will be weak, and it cannot resist the powerful brain keepers, such as thinking inertia, squeamishness, laziness, pastimes, social desires, etc.. So, it needs to be constantly guided and nurtured by us, giving it time to grow slowly bigger.

Although our childhood is gone, our work and lives are busy, and we are still distracted and influenced by outside technology and information, the awakening, nurturing, and cultivation of curiosity is still an important thing in our lives. In the pursuit of efficiency and utilitarianism, we still need to waste our time on things that mean little, but are fun. Maybe a small sapling (side project) that you unintentionally picked will become a huge tree (main project) that will support you for the rest of your life in the future.

As Maria Krikwa says in the opening testimonial of Curiosity: the most efficient minds are often the most able to let go of following those innermost impulses that are most childish.

May you always keep a pure curiosity and explore the unknown like a naked son with a rich heart after reading all the sails.

Dig a hole for yourself.

Now, like you reading this, I'm thinking: how do we cultivate curiosity inwardly in the face of years of pruning, cognitive biases, multiple social roles, busy work and life?

In the future, when virtual reality technology continues to develop, we can even communicate face-to-face in a virtual scenario, where technology intercepts almost all our senses, and even when brain-computer interface technology matures, we don't even need to speak and extend our expressions with our bodies, perhaps a single thought can convey our emotions and opinions. In the face of the rapid development of society, how can we resist the further 'truncation' of our curiosity by technology?

I've been thinking and organizing these answers, but because they're not complete, writing them out directly will feel like a tiger. Going forward I'll try to answer the questions above. You are also welcome to share your stories with Curiosity in the comments section.