On May 27, Beijing time, according to foreign media reports, on dry and rainless nights, Namibian aborigines "San people" often fall asleep in the light of the stars. They don't have electric lights, and they don't stay up late to catch up. But when they wake up the next morning, they sleep no longer than modern urbanites**

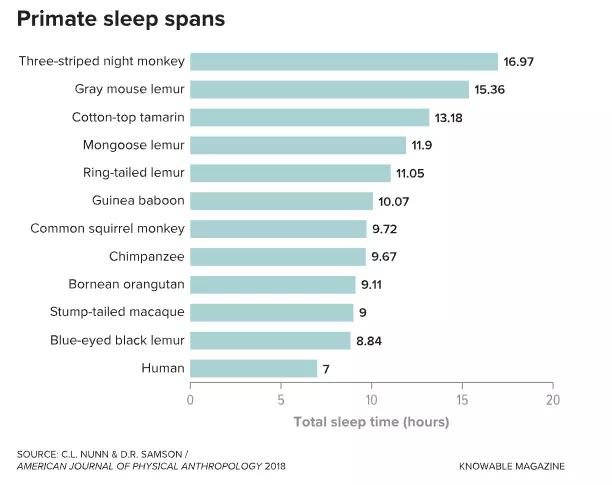

Davidsamsomson, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Toronto at Mississauga, points out that research shows that people living in non industrialized societies sleep less than seven hours on average. Compared with other primates, this figure is really surprising. Humans sleep shorter than any ape, monkey or lemur. Chimpanzees sleep 9.5 hours a day, and silky monkeys sleep about 13 hours. Although nocturnal monkeys strictly belong to nocturnal animals, they do not have much time to wake up, because they sleep as long as 17 hours a day.

Samson calls this difference the "human sleep paradox". "How can we sleep for the shortest time of all primates?" he said Sleep is crucial to our memory and immune function. According to a set of primate sleep prediction models established by scientists based on factors such as weight, brain volume and eating habits, humans should sleep for 9.5 hours a day. "There must be something wrong." Samson pointed out.

Samson and others' research on primates and non industrial social groups shows that human sleep is unusual in many ways. Not only do we sleep shorter than other primates, but we also sleep longer during REM sleep at night. The reasons why humans develop these peculiar sleep habits remain to be discussed, but some clues may be found in our evolution.

The picture shows the simple residence of the Kaza people, a Tanzanian hunter gatherer.

From hut to snail shell

Millions of years ago, our ancestors lived and even slept in trees. Today's chimpanzees and other apes still use trees as their beds. They bend branches into bowls, and then spread thin branches full of leaves. (apes such as gorillas sometimes make beds on the ground.)

As time went on, our ancestors gradually transferred from trees to the ground, and gradually formed the habit of sleeping on the ground. This means giving up all the benefits of sleeping in trees, such as avoiding the attacks of lions and other beasts.

Their sleep can not be seen from the fossils of human ancestors. Therefore, in order to understand how ancient humans slept, anthropologists can only start from the closest environment to ancient times - modern non industrial society.

"It is an honor and a great opportunity to work with these tribes." Samson said. He has carried out research work with the Kaza people, a hunter gatherer in Tanzania, and many tribes in Madagascar, Guatemala and other places. Subjects usually wear a sleep detector called actiwatch, which is equipped with a light sensor to record their sleep patterns.

The human evolutionary ecologist and anthropologist gandiyadish of UCLA also spent some time with the hazars, the tismans of Bolivia, and the SANS of Namibia. In a paper published in 2015, he evaluated the sleep of the three races and found that their average sleep time was only 5.7 to 7.1 hours.

It seems that humans have evolved to require less sleep than our primate cousins. Samson pointed out in a study conducted in 2018 that humans achieve this by shortening the duration of non REM sleep. Most REM sleep is associated with vivid dreams. This means that if other primates can also dream, we may spend the most time dreaming every night, and the time we sleep is not fixed.

In order to understand the evolutionary history of human sleep, Samson proposed the "social sleep hypothesis" in a paper published in the annals of anthropology in 2021. He believes that the evolution of human sleep mainly focuses on the theme of "safety", especially the safety of social life. Samson believes that the reason why humans have evolved a sleep mode with shorter duration, more flexible time and a higher proportion of REM sleep may be related to the threat that humans encounter after they begin to sleep on the ground. He also pointed out that sleeping in groups is another key point to increase safety during sleep.

"We should think of early human camps as snail shells." Samson pointed out. Humans may live together, share simple sheds, and light fires to keep warm and repel insects and ants. Some sleep, others watch.

"With the protection of this' shell ', you can always go back to the safe area and have a little sleep." Samson imagined. However, Samson and yetish have different views on this aspect. Samson said that hazars and a race in Madagascar often take naps; But yetish pointed out that according to his experience in this field, napping is rare.)

Samson also believes that these sleep "protective shells" promoted ancient humans to go out of Africa and enter colder regions. Therefore, he believes that sleep plays a key role in human evolution.

Are we really so special

Isabellacapellini, an evolutionary ecologist at Queen's University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, points out that this idea makes sense. In a 2008 study, she and her colleagues found that, on average, the greater the risk of predation, the less mammals sleep.

But capellini was not sure that human sleep was as special as it looked in other primates. She points out that the current data on primate sleep are all from captive animals. "We don't know much about the sleeping habits of these animals in the wild."

Due to stress, animals in zoos or laboratories may sleep less than in natural conditions. But capellini points out that because they do nothing all day, they may sleep longer. Moreover, the standard environment in the laboratory is 12 hours bright and 12 hours dark, which is quite different from the experience of animals in nature.

Niels rattenberg, a neuroscientist who specializes in bird sleep at the Max Planck Institute of ornithology, agrees with Samson that the evolution of human sleep is very interesting. But he also pointed out: "I think it largely depends on whether we measure the sleep time of other primates accurately."

We do have reason to doubt that. In a 2008 study, rattenberg and colleagues connected brain wave detectors to three wild sloths and found that they slept 9.5 hours a day. In a previous study on the artificial breeding of sloths, the sleep time of sloths was recorded as long as 16 hours.

Sleep researchers would benefit a lot if they could get more data from wild animals. "But there are great technical challenges in doing so." Rattenberg pointed out, "although sloths are relatively tame in the research process, I feel that primates may want to take off the detection instruments."

After scientists have a better understanding of the sleep habits of wild primates, perhaps the length of human sleep will not be so short. "Every time we claim how special human beings are, once we have more data, we will realize that we are not that special."

Fireside conversation

Yedish specializes in the study of sleep in small-scale societies and has cooperated with Samson in the study. "According to his description, I also believe that sleeping in groups is a way to solve the problem of night safety." "But I don't think this is the only solution," yetish said

He noted that the tisman people sometimes built walls in their houses, which provided a certain degree of security even if no one was watching. In the morning, some people will tell yedish which animals they heard last night. Most people wake up at night after hearing the sound, which adds another layer of security.

Yedish pointed out that sleeping together is a natural derivative of these small-scale societies, whether or not they are threatened by beasts. "In my opinion, people in this kind of society almost never have time to be alone."

Yetish described a typical night spent with the tisman people: after finishing all kinds of work during the day, people cooked meals and came to the campfire. They first shared food with each other, and then spent time by the campfire at night. Eventually, the children and their mother went to bed first, while the others stayed by the fire, chatting and telling stories.

So yetish suggested that ancient humans might be willing to "sacrifice" some sleep time to exchange information and culture by the campfire. "In this way, the night time can also be harvested." Our ancestors may have actively compressed their sleep time because they had more important things to do at night than rest.

Lack of sleep

Of course, "how long do we sleep" and "how long do we want to sleep" are two completely different questions. Samson and others have asked hazars how they feel about their sleep. Results among the 37 people, 35 said they slept "just right". Their average sleep time per night is about 6.25 hours. But they wake up so often that they actually spend more than nine hours in bed.

In contrast, a study conducted on nearly 500 Chicago residents in 2016 showed that they basically slept in bed, and the total sleep time was basically the same as that of hazars. But in a 2020 survey of American adults, 87% of the respondents said they didn't feel well rested at least one day a week.

Why? Samson and yetish point out that our sleep problems may be related to stress or chaotic circadian rhythms. It may also be that we all sleep alone now, which is inconsistent with the evolution of human sleep. In every tossing and turning night, we are actually experiencing the deviation between evolution and reality. "Nowadays, almost all of us live isolated lives, which may also affect our sleep."

Samson pointed out that a better understanding of the evolution of human sleep might help people improve their sleep, or make people feel satisfied with their sleep.

"People in many developed countries feel that they have problems sleeping." But insomnia may mean that the ability to be highly alert is an evolutionary advantage.

Yedish points out that studying sleep in these small societies has "completely" changed his perspective on sleep. "The western world pays too much attention to sleep, which is quite different from people in these environments. People here don't force them to sleep for many hours, they just sleep." (leaves)