Two new studies underscore the importance of using antibiotics wisely* One study found that antibiotics can increase the risk of fungal infection by causing defects in the activity of the intestinal immune system, * while another study showed that the heavy use of antibiotics in old age is related to the incidence rate of Crohn's disease and other inflammatory bowel diseases.

Although a lot of attention has correctly pointed to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance, this is not the only reason why we should be cautious about the frequency of these common drugs. Two new studies strongly remind us that antibiotics are not harmless drugs and should only be taken when necessary.

The first study was an international collaboration between us and UK researchers to understand why people treated with antibiotics in hospitals tend to experience greater rates of fungal infection. The focus is on a particularly dangerous fungal infection, invasive candidiasis.

Many people may be familiar with a common yeast infection called thrush. This is caused by a fungus called Candida. In general, these infections are superficial, but in some people, they can enter the blood and cause invasive candidiasis.

It has been speculated that antibiotics can increase a person's risk of invasive candidiasis through the intestine. But until now, it is not clear how this process is carried out.

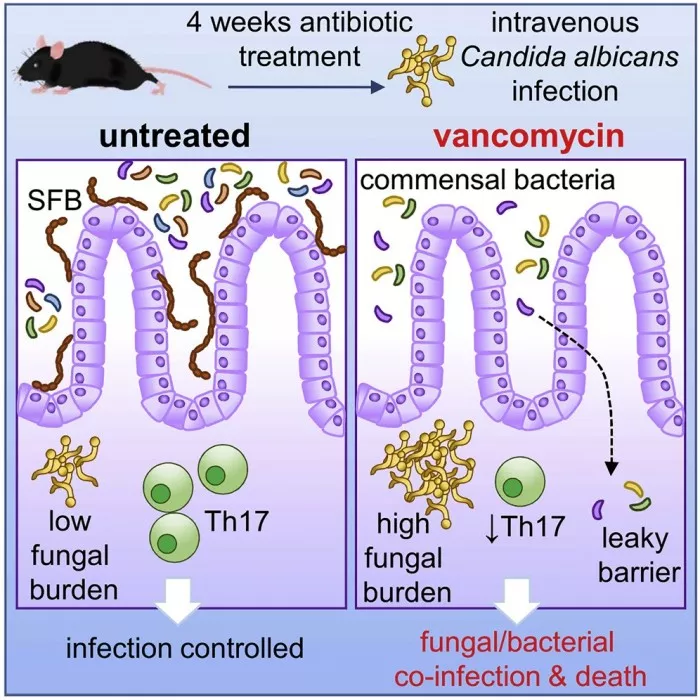

In a series of animal experiments, the new study first confirmed that the use of antibiotics did worsen fungal infection. Fungal infections have intensified in the gut after antibiotic use, but it is still unclear what makes animals so sick.

The researchers found that antibiotics caused an abnormal immune response in the intestine, which in turn caused bacteria in the intestine to enter the blood. This causes animals to suffer from both bacterial and fungal infections, making them more ill than animals that are not treated with antibiotics.

"To figure out why this happens, we analyzed immune cells in the gut to figure out how antibiotics lead to defective antifungal immune response," lead author Rebecca Drummond explained in an article in the conversation. "Immune cells in the gut produce small proteins called cytokines as information to other cells. We found that antibiotics reduced the number of these cytokines in the gut, which we believe is part of the reason why antibiotic treated mice were unable to control fungal infection in the gut or prevent bacterial escape."

The researchers then found that treating mice with immune enhancing cytokines could help offset the harm of antibiotics. This finding points to a potential treatment for those at high risk of fungal infection but who need key antibiotics.

"We know that antibiotics worsen fungal infections, but it's surprising to find that bacterial co infections can also develop through these interactions in the gut. These factors together can form a complex clinical situation - by understanding these root causes, doctors will be able to treat these patients better and effectively," Drummond said

The second study, which has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal but will be published at the upcoming digestive disease week meeting, found a significant correlation between antibiotic use and the development of inflammatory bowel disease in people over the age of 60.

"In the elderly, we think environmental factors are more important than genetic factors," said Adam Faye, lead researcher at the Grossman School of medicine at New York University. "When you look at young patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, they generally have a strong family history. But this is not the case in the elderly, so something in the environment is really inducing it."

To investigate the potential relationship between antibiotic use and the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the researchers looked at nearly 20 years of health record data, including more than 2 million people aged 60 to 90.

The study found a significant dose-response relationship between IBD risk and antibiotic use. One course of antibiotics increases a person's risk of IBD by 27% within five years; The risk of two courses of treatment increased by 55%; The risk of three courses of treatment increased by 67%; The risk of four courses of treatment increased by 96%; Five or more courses of treatment increased the risk by 236%.

This association is consistent in most types of antibiotics, and the risk is greatest in the first one to two years after antibiotic use.

Future research will need to unravel what mechanisms may underlie this association, Faye said. He speculates that antibiotic induced disruption of the intestinal microbiome may play a role in this relationship.

Finally, Faye made it clear that these findings do not mean that people need to give up antibiotics completely. According to Faye, if you need these key drugs to treat infections, you shouldn't avoid using them. But he does suggest that doctors should be more cautious when prescribing these drugs to elderly patients without clear infection.

"Antibiotic management is important; but avoiding antibiotics at all costs is not the right answer. If you're not sure what you're treating, I'll be cautious. If a patient has a significant infection and needs antibiotics, they shouldn't be rejected because of these findings," Faye said

The fungal antibiotic study was published in cell host and microorganism 00219-0).