Stem cell therapy has shown great prospects in many fields, but one application that scientists are particularly excited about is the next generation treatment of Parkinson's disease. An experimental team in this field has proved that the implantation of carefully cultured stem cells into mice can significantly recover the typical motor symptoms of the disease. Now they are looking at the upcoming human trials.

Parkinson's disease is considered the main target of innovative stem cell therapy because the disease can be traced back to a specific type of cell degeneration in specific areas of the brain. Neurons in the substantia nigra are a structure of the midbrain responsible for producing dopamine that helps control activities such as movement.

The loss of these neurons is the cause of motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease, so using stem cell therapy to replace them is a very attractive idea, and the idea has begun to migrate from animal experiments to humans. In a world-class trial conducted in Japan in 2018, patients with Parkinson's disease implanted stem cell-derived precursor cells into their brains, where they developed neurons that produce dopamine, and some subjects are said to have performed well.

Similar early trials are currently underway in the United States, and scientists are trying to determine the safety and effectiveness of using induced pluripotent stem cells (IPS) to restore normal movement in patients with Parkinson's disease. These iPS cells began as harvested adult cells and were treated with reprogramming factors to restore them to embryonic state. The second stage is to expose them to more growth factors and turn them into dopamine producing neurons.

Scientists at Arizona State University have been experimenting with this process and testing their designed neurons in mice in a proof of concept study. Their idea is to optimize the method of producing these cells, adjust them, and then see which version can maximize the improvement of Parkinson's symptoms in rodents, and preferably make the technology closer to clinical application.

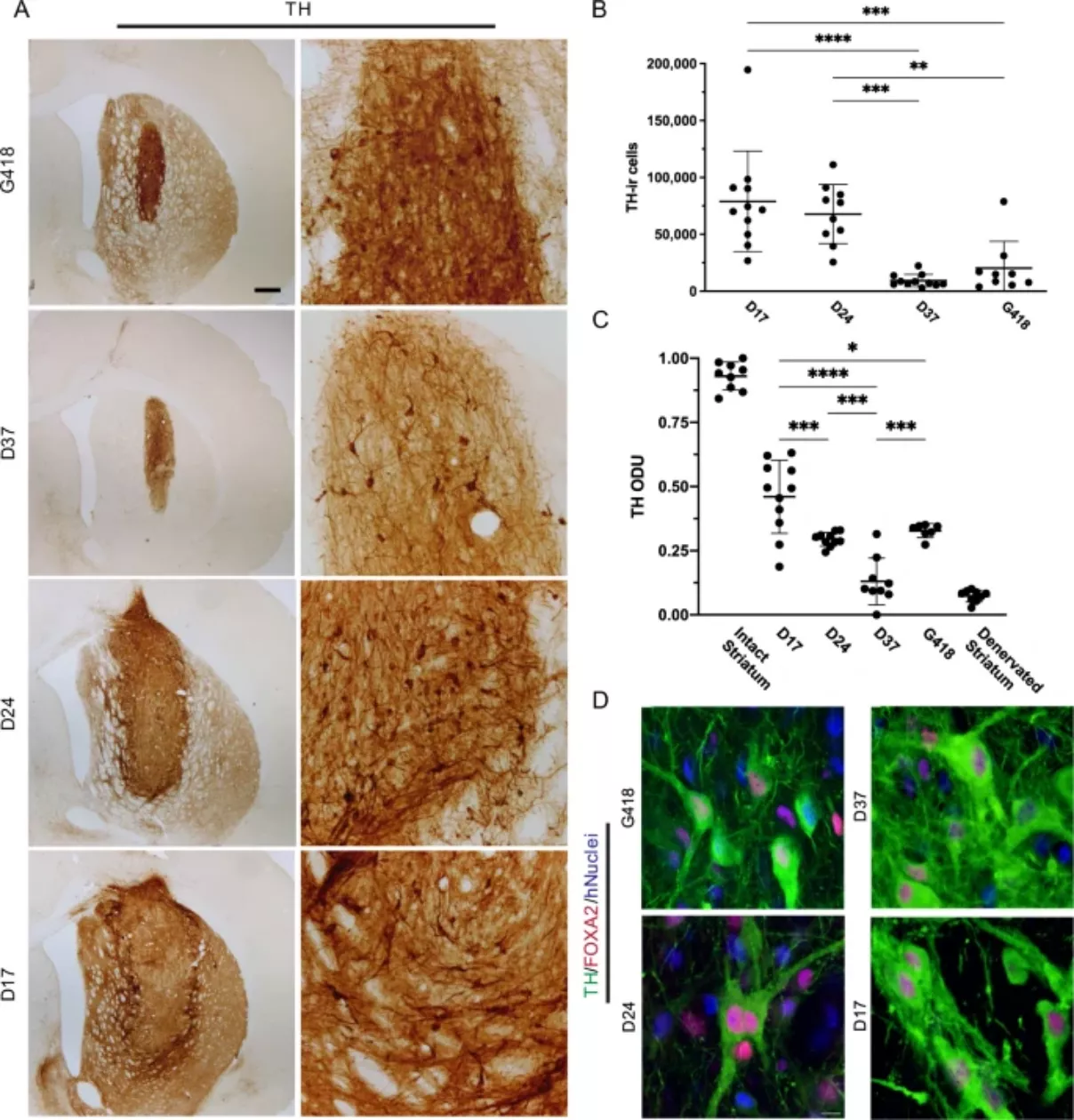

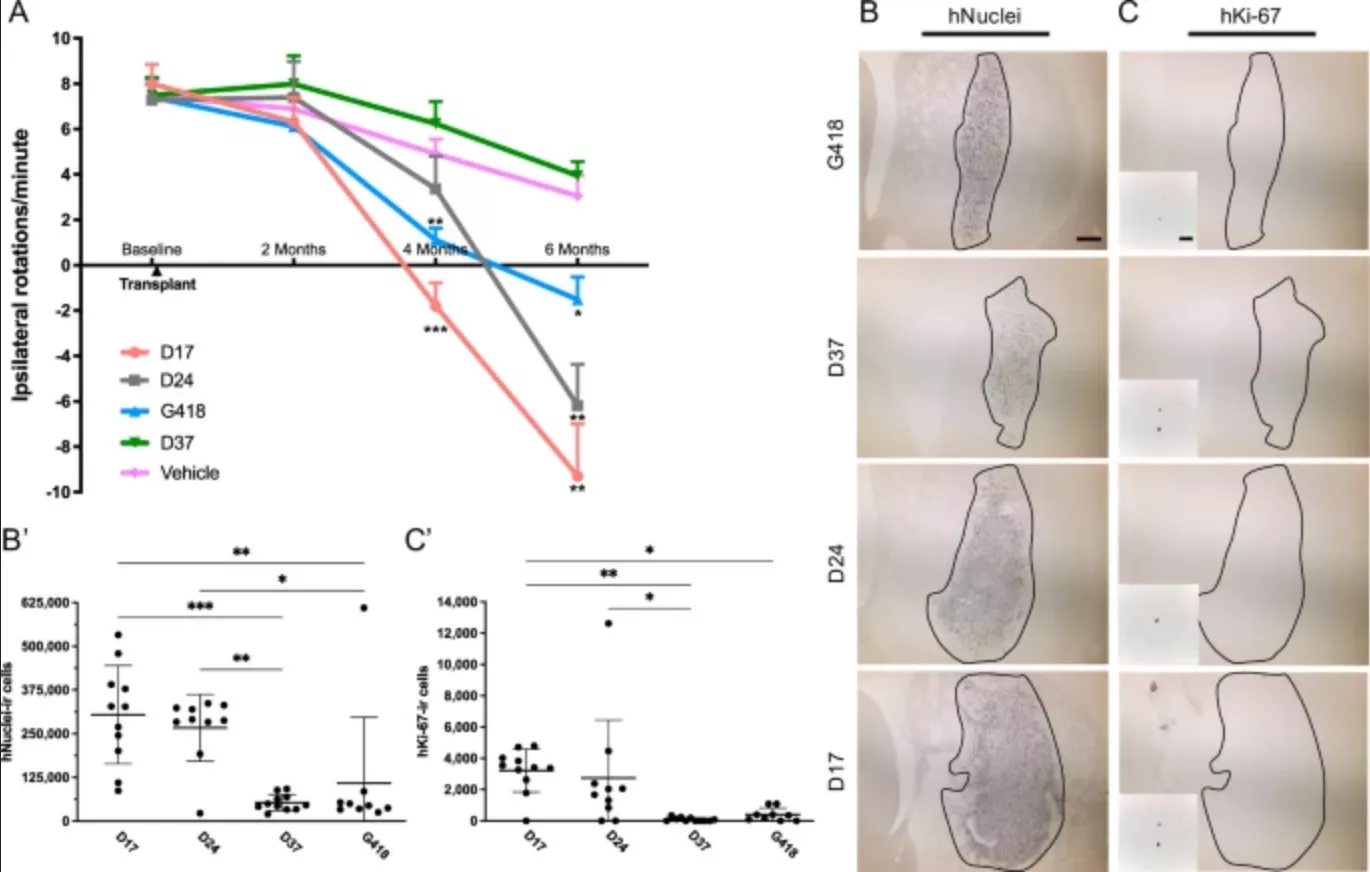

This means that in the second stage of reprogramming, stem cells are placed in different time periods, and different cell populations are cultured for 17, 24 or 37 days respectively. Results the research team found that the 17 day stem cells were significantly better than other types of stem cells. When the stem cells were transplanted into the mouse brain, their motor symptoms recovered significantly.

In addition, the dose was also found to be the key. The effect of a small number of stem cells was negligible, while a large number of stem cells entered the brain and combined with neural tissue, and then formed synapses and produced dopamine. Eventually, this allowed the treated mice to completely reverse the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Following these promising results, the technology will now include a small number of similar technologies being studied in humans, which is considered to be a first experiment. It will focus on specific populations of people with Parkinson's disease, who are known to have mutations in their Parkinson's gene. Although these patients experienced a decline in motor symptoms, they did not have cognitive decline or dementia, which scientists say makes them ideal candidates for testing.

"We are very excited about the opportunity to help people with this genetic form of Parkinson's disease, but the experience gained from this trial will also directly affect people with sporadic or non genetic forms of the disease," said Jeffrey kordower, author of the study