The evolutionary morphology laboratory led by Shigeru kuratani of RIKEN pioneer research cluster (CPR) in Japan, together with its collaborators, found evidence that the mysterious ancient fish vertebrate palaeospondylus may be one of the earliest ancestors of limb animals, including humans It was unveiled in the journal Nature on May 25th and published in the past.

Palaeospondylus is a small fish vertebrate, about 5cm long. It has an eel like body and lived in the Devonian period about 390 million years ago. Although the fossils are very abundant, their small size and poor quality of skull reconstruction through CT scans and wax models have made it very difficult to determine their position in the evolutionary tree since they were discovered in 1890. Researchers believe that it has common characteristics with jaw fish and jaw less fish, and its body as a mystery has always puzzled evolutionary scientists. Of several unusual features, the most puzzling is the absence of teeth or bones in the fossil record.

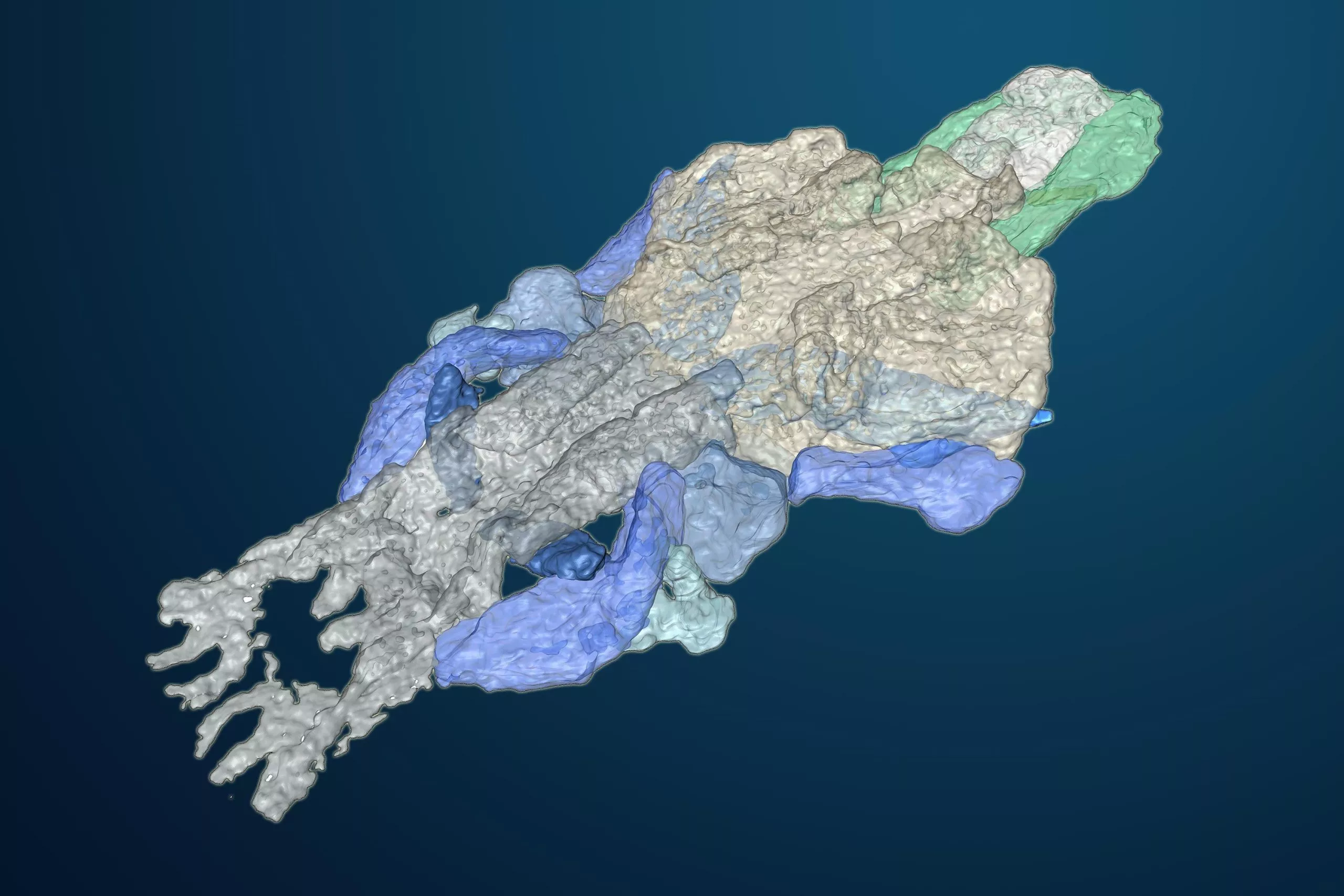

In order to solve some of these problems, researchers used the powerful RIKEN SPring-8 synchrotron to generate high-resolution micro CT scanning images using the X-rays radiated by the synchrotron. In addition, unlike most studies that use excavated fossil heads, the new study uses carefully selected fossils in which the heads are still completely embedded in the rock. Tatsuya Hirasawa, the first author of the paper on the study, said: "selecting the best specimens for micro CT scanning and carefully trimming the rocks around the skull fossils enable us to improve the scanning resolution. Although it is not a very cutting-edge technology, these preparations are undoubtedly the key to our achievements."

High resolution scanning shows several important features. First, the researchers found three semicircular tubes that clearly showed the shape of the inner ear of jaw vertebrates. This solves a problem because previous studies have shown that palaeospondylus is evolutionarily closer to primitive jawless vertebrates. Next, they discovered key skull features and classified palaeospondylus into the quadruped category, which is composed of quadrupeds, quadrupeds and their closest ancient relatives. Some analyses have shown that palaeospondylus is more closely related to quadrupeds with limbs than to many other known quadrupeds that still retain fins.

Unlike other quadrupeds, however, teeth, bones and paired appendages have never been associated with the fossil palaeospondylus, although these features are easily found in fossils of other animals living at the same time and place in achanarras fish bed, Scotland. The lack of these features can be explained by the division of a set of developmental features, resulting in a larval like body. "It may never be known whether these features were lost in evolution or whether normal development was frozen in fossils. Nevertheless, this asynchronous evolution may have promoted the development of new features such as limbs," Hirasawa said

Kuratani and his team did not limit their research on the evolution of early vertebrates to the fossil record. They also use molecular biology and genetics to study the developmental embryos of key modern vertebrates. "The strange shape of palaeospondylus is similar to that of quadruped larvae, which is very interesting from the perspective of developmental genetics," Hirasawa said. "With this in mind, we will continue to study the developmental genetics that bring about this and other morphological changes, which occur in the transition from water to land in the history of vertebrates."