An energy research team led by the University of Minnesota twin cities has developed a breakthrough device that electronically converts one metal into another so that it can be used as a catalyst to accelerate chemical reactions The device, known as the "catalytic condenser", proved for the first time that alternative materials changed electronically can provide new characteristics, making chemical treatment faster and more effective.

The invention paves the way for new catalytic technologies using non noble metal catalysts, which can be used in important applications such as storing renewable energy, manufacturing renewable fuels and manufacturing sustainable materials.

The study was published online in [JACS Au], a leading open Journal of the American Chemical Society( https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacsau.2c00114 ) 》Come on. The team has a temporary patent for the device and is working with the office of technology commercialization at the University of Minnesota.

In the last century, chemical processing has relied on the use of specific materials to promote the manufacture of chemicals and materials used in our daily life. Many of these materials, including precious metals, such as ruthenium, platinum, rhodium and palladium, have unique electronic surface properties. Because they can be used as both metals and metal oxides, they are very important for controlling chemical reactions.

The general public may be most familiar with this concept, as the theft of catalytic converters on cars has increased. Catalytic converters are valuable because they contain rhodium and palladium. In fact, palladium may be more expensive than gold. These expensive materials are often in short supply all over the world and have become a major obstacle to technological progress.

In order to develop this method of adjusting the catalytic properties of alternative materials, researchers rely on their understanding of the behavior of electrons on the surface. The team successfully tested the theory that adding and removing electrons from one material can turn metal oxides into properties that mimic another material.

"Atoms really don't want to change their number of electrons, but we invented a catalytic condenser device that allows us to adjust the number of electrons on the surface of the catalyst," said Paul dauenhauer, a MacArthur researcher who led the research team and a professor of chemical engineering and materials science at the University of Minnesota. "This opens up a new opportunity for chemistry to play the same role as valuable materials."

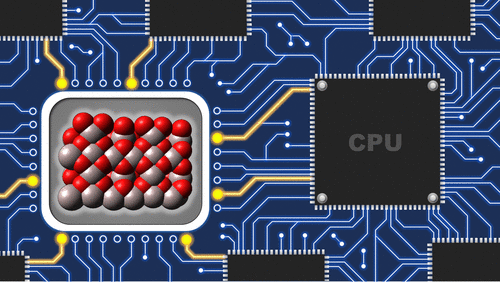

The catalytic condenser device uses a combination of nano films to move and stabilize electrons on the surface of the catalyst. This design has a unique mechanism to combine metals and metal oxides with graphene, combining rapid electron flow with adjustable chemical surfaces.

"Using various thin-film technologies, we combine nanoscale alumina films made of low-cost and rich metal aluminum with graphene, and then we can adjust them to have the characteristics of other materials," said tzia Ming onn, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota who manufactured and tested catalytic condensers. "The substantial ability to adjust the catalytic and electronic properties of the catalyst exceeded our expectations."

As a platform equipment, the design of catalytic condenser has a wide range of utility in a series of manufacturing applications. This versatility comes from its nano fabrication, which uses graphene as a favorable component of the active surface layer. The ability of the device to stabilize electrons (or the loss of electrons called "holes") can be adjusted by changing the composition of the strong insulating inner layer. The active layer of the device can also add any basic catalyst material and additional additives, and then can be adjusted to achieve the characteristics of expensive catalyst materials.

"We believe that the catalytic condenser is a platform technology that can be implemented in a large number of manufacturing applications. The core design insights and novel components can be modified into almost any chemistry we can imagine," said Dan Frisbie, professor and Dean of the Department of chemical engineering and materials science at the University of Minnesota and a member of the research team

The team plans to continue their research on catalytic condensers and apply them to precious metals to solve some of the most important sustainability and environmental problems. With financial support from the U.S. Department of energy and the National Science Foundation, several parallel projects are already under way to store renewable electricity in the form of ammonia, key molecules for the manufacture of renewable plastics, and clean gas waste streams.