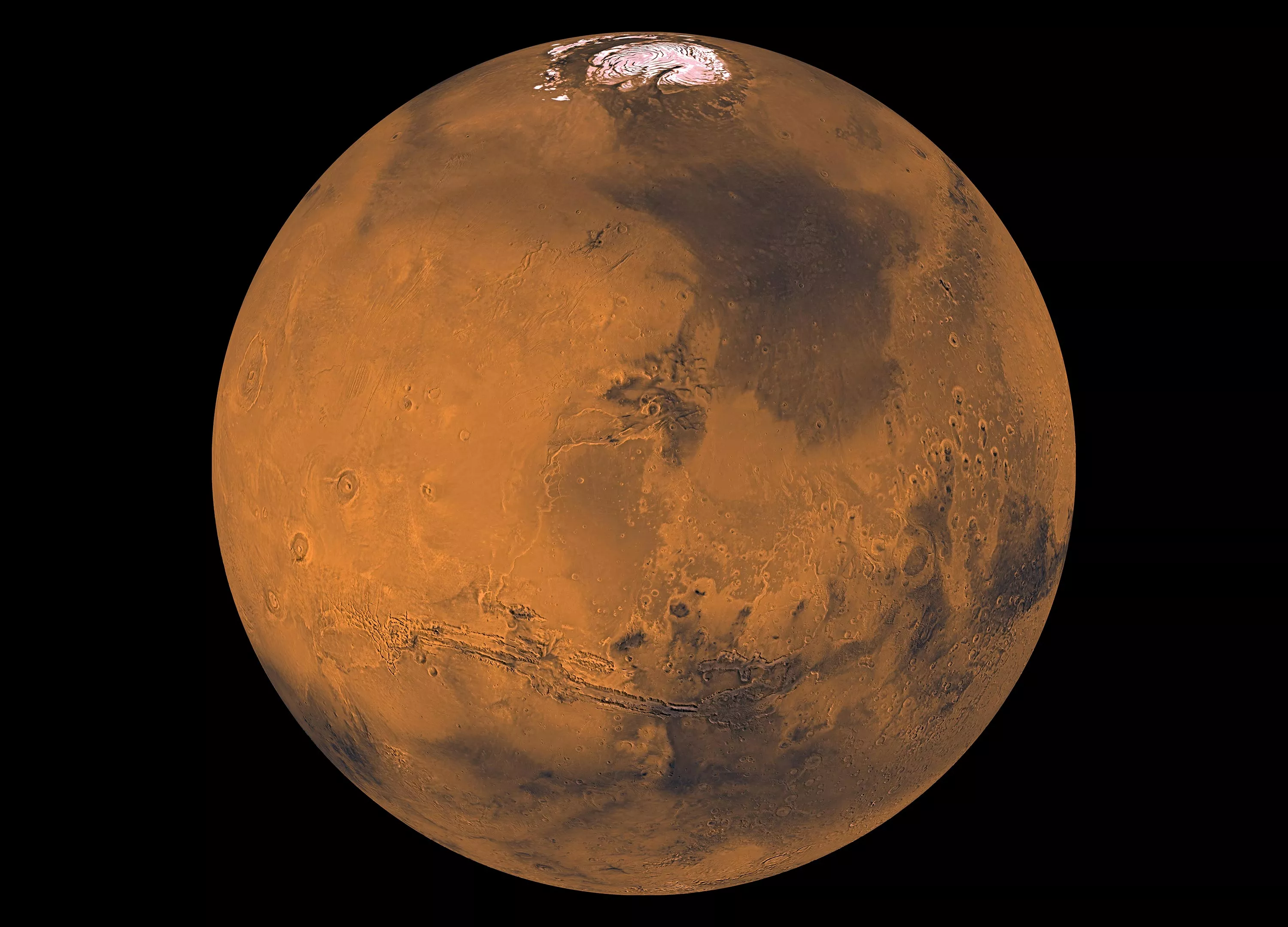

In a haze, NASA's perseverance parachuted to the dust surface of Mars in February 2021. Over the years, the probe has been gliding and collecting samples in an attempt to answer the questions raised by David Bowie in life on Mars in 1971. Although NASA doesn't really plan to send samples back to earth until around 2030, materials from Mars have been studied - in the form of meteorites.

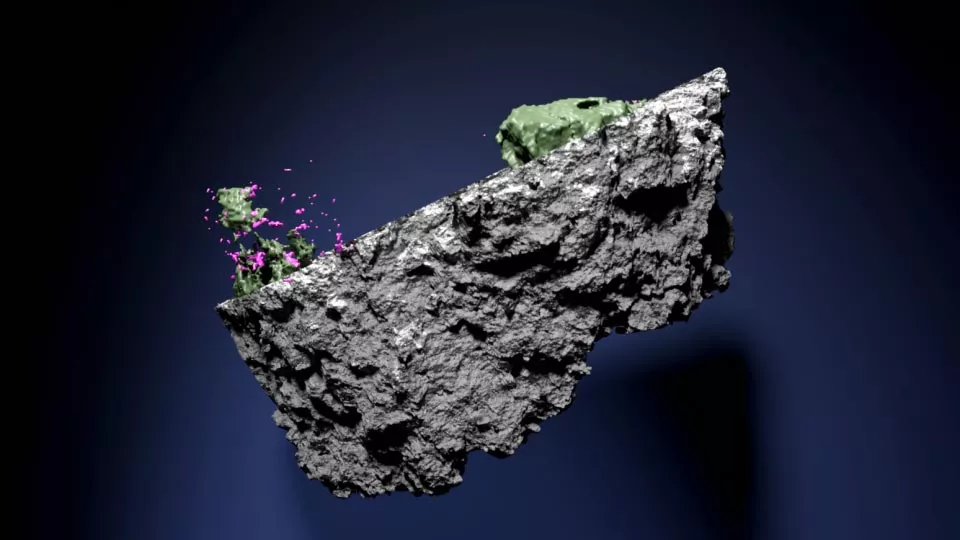

In a new study published in science advances on May 11, 2022, an international research team used advanced scanning technology to study a meteorite about 1.3 billion years old.

Josefin Martell, a Ph.D. student in geology from Lund University, said: "since water is the core issue of whether there has been life on Mars, we want to study how much meteorite reacts with water when it is still part of Martian bedrock."

To answer whether there are any major hydrothermal systems - usually an environment conducive to life - the researchers used neutron and X-ray tomography. X-ray tomography is a common method of examining objects without damaging them. Neutron tomography is used because neutrons are very sensitive to hydrogen.

This means that if a mineral contains hydrogen, it is possible to study it in three dimensions and see the location of hydrogen in meteorites. When scientists study materials from Mars, hydrogen (H) is always interesting because water (H2O) is a prerequisite for life as we know it. The results show that a relatively small part of the sample seems to react with water, so it may not be a large hydrothermal system that caused this change.

"A more likely explanation is that the reaction occurred after a small piece of underground ice melted in a meteorite impact about 630 million years ago. Of course, this does not mean that life cannot exist elsewhere on Mars or at other times," Josefin Martell said.

The researchers hope that their results will be helpful when NASA brings back the first samples from Mars around 2030, and there are many reasons to believe that current neutron and X-ray tomography technology will be useful in this case.

Josefin Martell concluded: "it would be very interesting if we had the opportunity to study these samples at the European sputtering source (ESS) at Lund's research facility, and it would become the most powerful neutron source in the world."