Pancreatic cancer is one of the major causes of cancer-related death. Its prognosis is devastating. Less than 10% of patients can survive for more than five years after diagnosis. One factor that makes pancreatic cancer so difficult to treat is that it builds a scar like tissue cocoon called cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs), which prevents chemotherapy and other treatments from entering.

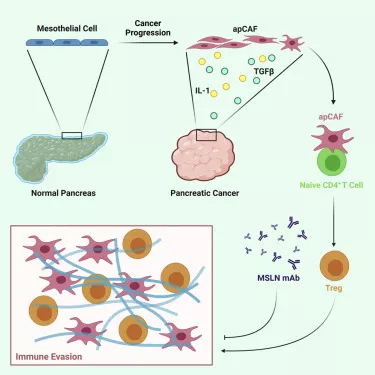

In the new study, scientists from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center found another way this barrier works to protect cancer. Some CAFs have a particularly annoying "trick" - they present antigens on their surface, making immune cells that attack tumors lose their resistance. These antigens convert T cells into regulatory T cells (Tregs), thereby shutting down further immune responses in the region.

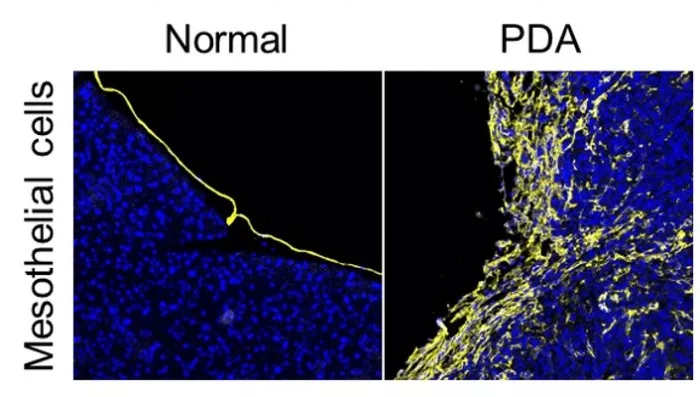

In order to study the method of counterattack, the researchers conducted pedigree tracking against the original presentation CAFs (apcafs). This process allows the team to track how these troublesome cells develop over time, because a healthy pancreas can turn into cancer. They found that apcafs begin with mesothelial cells, which form a protective layer in organs and other tissues.

With this new understanding, researchers have tried a potential way to break through this obstacle. When testing mice with pancreatic cancer, the team injected the animals with antibodies against mesothelin, a protein component of mesothelial cells. Sure enough, apcafs can no longer interfere with immune cells.

The findings pave the way for a possible new treatment for human pancreatic cancer by pairing anti mesothelin antibodies with existing immunotherapies, the researchers said. After antibodies weaken the defense system, immunotherapy can "break through the door" to help conquer tumors.

Of course, more work needs to be done in animal trials before it can be used in human patients. But one day, pancreatic cancer may no longer be a death sentence.

The study was published in cancer cells 00173-8).