After the arrival of the COVID-19 epidemic, everyone must be very familiar with the vaccine. For example, newcoronavirus vaccine can activate our immune system and help the body identify and defend against the invading novel coronavirus. Since the birth of the first vaccine, it has helped mankind prevent many fatal diseases. Although vaccines are usually targeted at bacteria or viruses, can vaccines do more? For example, help eliminate cancer cells that also grow like parasites.

With this idea, the concept of cancer vaccine against cancer cells came into being. In recent years, cancer vaccines have made great progress. Generally speaking, preventive cancer vaccines are mainly aimed at cancer caused by virus infection. For example, by preventing human papillomavirus or hepatitis B virus infection, this part of cancer vaccine can prevent cancer caused by two types of viruses.

In addition, most of the cancer vaccines mentioned now refer to therapeutic vaccines, that is, to help tumor patients stimulate the immune system to obtain stronger anti-cancer ability.

These vaccines target specific surface proteins expressed by tumor cells and help the immune system recognize these proteins, namely tumor antigens. The abnormally high expression proteins of some cancer cells are very good vaccine targets. For example, prostate cancer cells usually overexpress prostate acid phosphatase (Pap). FDA approved a cancer vaccine against PAP in 2010.

However, this kind of vaccine has some shortcomings. They mainly rely on the main histocompatibility complex to present antigen proteins to T cells, just like finding virus antigens.

The antigen presentation characteristics and immune activation ability of each tumor patient are very unique, which means that the development of universal cancer vaccine will be more difficult.

In addition, tumors can also escape immune attack by mutating proteins on the surface, which will further reduce the efficiency of the vaccine. This is just like that after some protein mutations of the virus, the protection of the vaccine will also decline.

Today, a new study published in the journal Nature has brought a newly designed cancer vaccine, which can induce different T cells and natural killer cells to attack cooperatively, so as to play a broader immune function.

The newly designed vaccine targets two types of surface proteins - mica and MICB (Mica / b). When the human body suffers too much DNA damage due to cancer, these two stress proteins will be produced in large quantities. Mica / B can be produced in a large number in a variety of cancer cells, but it can hardly be detected in healthy cells, which determines its tumor specificity.

In addition, it can become a ligand to activate T cells and natural killer cells (NK cells) and accelerate the immune system to eliminate tumors.

However, cancer cells will not let this threat happen. They will decompose and cut Mica / B through proteolysis, reducing the possibility of their activating immune cells, so as to avoid immune attack.

However, the new vaccine can prevent the tumor from cutting Mica / B, so as to improve the level of Mica / b protein on the tumor surface. This process can activate dendritic cells to present tumor antigen to T cells and enhance the cytotoxicity of NK cells.

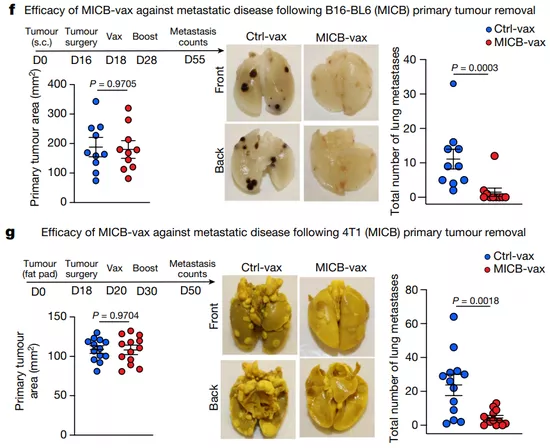

The researchers tested the effect of the vaccine in animal models. They found that using the vaccine in tumor mice can significantly reduce tumor metastasis and reduce the growth rate of cancer cells.

Compared with the control group, the tumor mice injected with the vaccine will obviously gather more kinds of immune cells in their tumor samples. The number of CD8 + T cells and CD4 + T cells is 17.9 and 29.3 times higher than that of the control group, and the number of NK cells is nearly 40 times higher.

This indicates that the injection of various tumor growth factors can also fundamentally solve the problem of tumor growth and necrosis.

The researchers point out that these preliminary results show that Mica / B-based cancer vaccine can activate effective tumor immunity, and they plan to evaluate its effectiveness and safety in humans in future clinical trials.